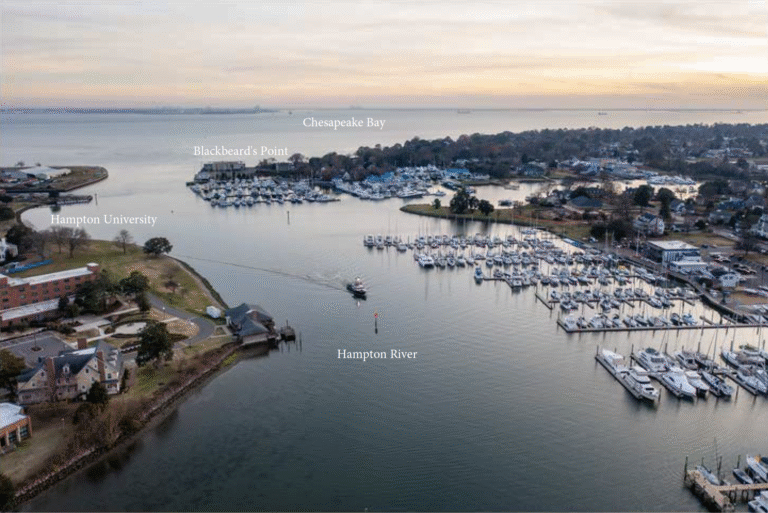

Hampton University comes up big in Blackbeard’s Lost Head.

I grew up within sight of Hampton University but only knew it as a prestigious school for smart people. I also knew it was an Historically Black College and University (HBCU) originally founded for freedmen and freedwomen. I wasn’t inclined to visit the school or wander the campus. There were adults there and austere buildings that represented anything other than a good time.

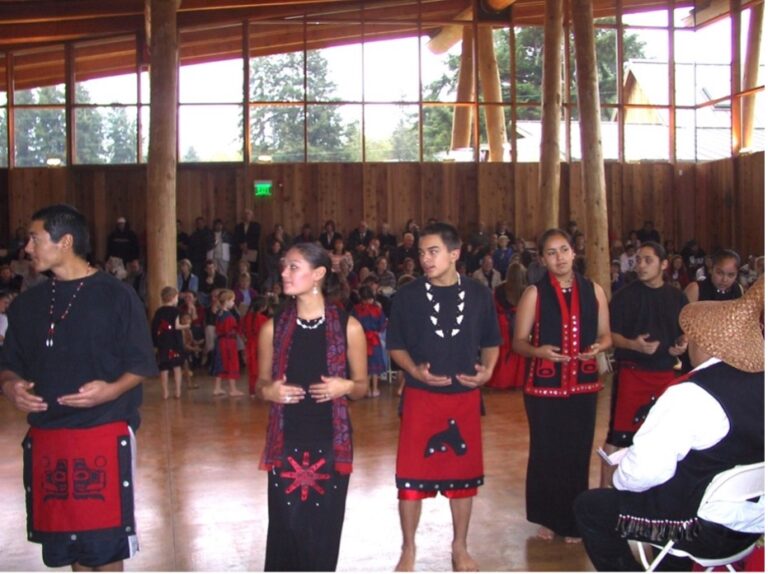

It was only when I moved away to Seattle and started working for the Tulalip Tribes that I learned that Hampton had been a school for Native Americans from 1877-1923. In a chance meeting, I learned that the father of Tulalip Chairman Stan Jones went to school there. He asked me to get him a letterman’s jacket the next time I traveled back to Hampton to see family. The purchase of the letterman’s jacket led me to the Hampton University Museum where I got an education on Indian education at Hampton University.

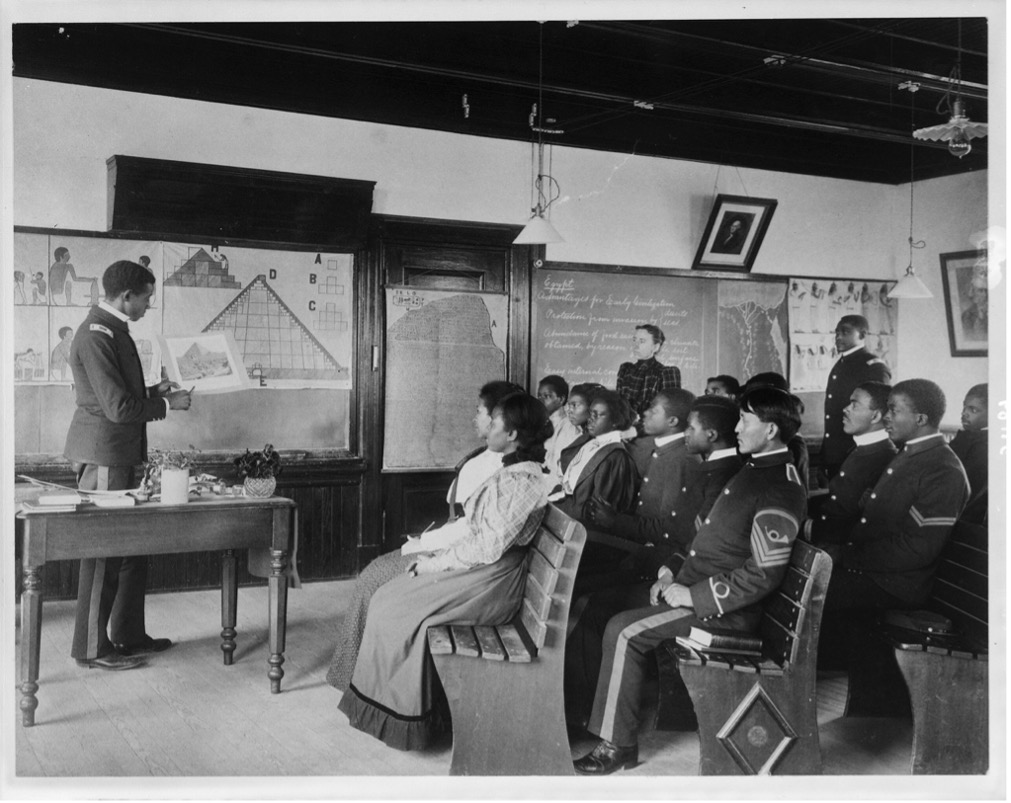

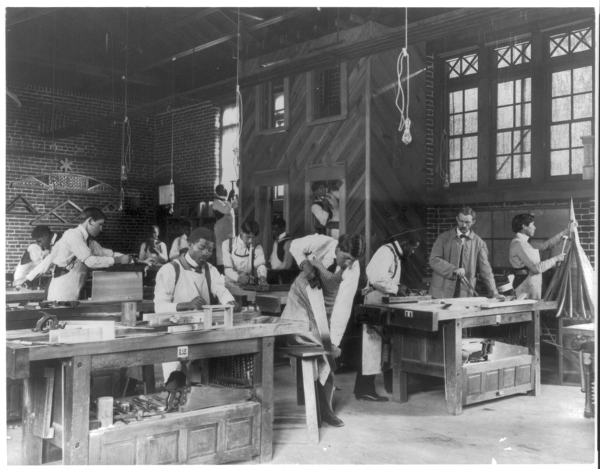

The first Native students were prisoners from the Indian Wars and had no choice but to attend the school in 1877, but even that was short lived. A few stayed, but most simply went home to their families. From that point forward, the school was voluntary and selective. Native students were largely sponsored with private money and therefore free of the most damaging and demoralizing policies of the government run schools funded by the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA). At Hampton, the goal was less about assimilation, and more about teaching skills needed to survive in the industrial and agricultural revolution. All of this is well documented and worth exploring if you’re so inclined.

Eventually, the school was flooded with applications and had to turn many Native Americans away. The conditions for admission were simple: “Sound health, good character, age not less than fourteen years and not more than twenty-five, ability to read and write intelligibly, knowledge of arithmetic through long division, intention to remain throughout the whole course of three years and to become a teacher.”

This doesn’t mean that it was all roses for Native people attending the school. Many died from illness, including babies born to Native students. The tragedy of lost cultural ties and the sadness of being separated from their families was difficult. Traveling home between school sessions was out of the question. It was expensive, especially when home was the far reaches Montana, Idaho and Washington State. Many remained on university grounds for two to three years before graduating and returning home.

The Indian graveyard at Hampton is testament to the struggles of many Native people who attended Hampton. But the care in which these courageous people were memorialized tells you something about the school itself. I would highly recommend visiting the Indian graveyard on the grounds of Hampton University. It tells a story of tragedy and courage and deep respect.

Hampton University Today

Hampton University today is a prestigious private HBCU school (Virginia Coastal magazine identified it as the 2023 Best Private College in the Tidewater region). Its economic contribution to the City of Hampton is significant, providing hundreds of jobs on campus and spawning thousands more in the area economy. But it wasn’t always that way.

When it was first established as a school for freedmen in 1868, students lived in tents and money was scarce. Bi-racial Christian organizations (primarily American Missionary Association) raised money for the school. A highly successful and legendary student choir in the early twentieth century toured northern states and is credited with shoring up the school’s finances. Virtually every pop music star today owes a debt of gratitude to this choir who brought Black music to the masses.

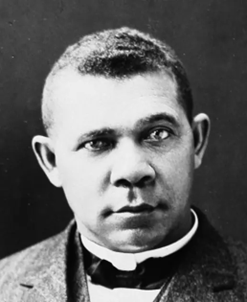

Perhaps Hampton’s most famous graduate is Booker T. Washington, a man who was born into slavery then on to fame as an educator and administrator. He became an American hero, consulted with presidents, and was instrumental in leading the Tuskegee Institute to national prominence.

Hampton University was founded by a guy named Samuel Chapman, a Civil War Union General. He had been assigned by the Freedmen’s Bureau to address issues of education among former slaves who had gathered behind Union lines on the Virginia peninsula.

He was born in Hawaii to missionary parents.

Chapman, from all accounts, was a profoundly good person and today rests right next to the Native graveyard. I find his grave marker to be peculiar. It’s a crudely chiseled volcanic rock from Hawaii that has no business being in the middle of the curated, smooth and conventionally shaped monuments. At his feet is a small boulder from a mountain in Massachusetts where he went to college.

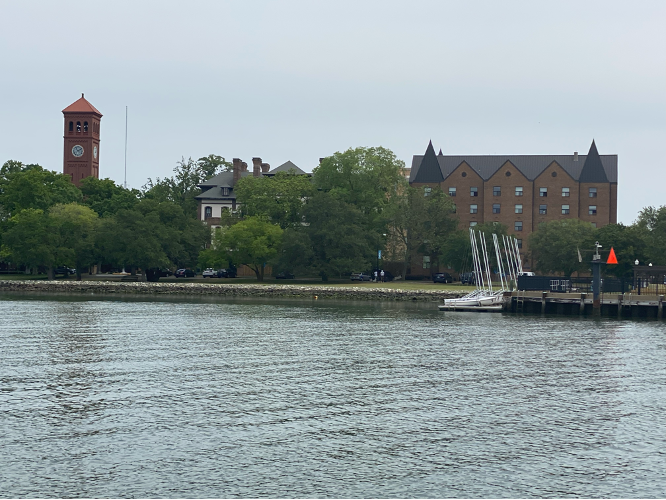

The Wigwam Building at Hampton University

Indian students at Hampton were housed in Wigwam Building, which was constructed in 1878. It was originally built to house male students. The building was ceremoniously restored 2018 with financial support from the National Park Service. The building was constructed by Indian students themselves.

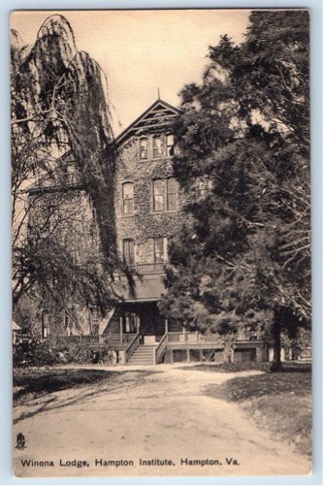

Female students were housed at the Winona Lodge which is long gone. But here’s a postcard of the old building that I found on Ebay.