Blackbeard’s Lost Head is set on the Port Gamble S’Klallam Tribe, or sometimes called “Little Boston,” a name supposedly coined by 19th century Bostonian traders who upon anchoring in Port Gamble Bay decided the village and surrounding geography reminded them of their home.

Somewhere along the line, generations of Tribal Members made the name Little Boston their own and today, one can see the Red Sox logo mixed in with Native motifs on t-shirts, hats and even artwork. Tribal Members are hardcore Mariner fans, but the Red Sox are close second.

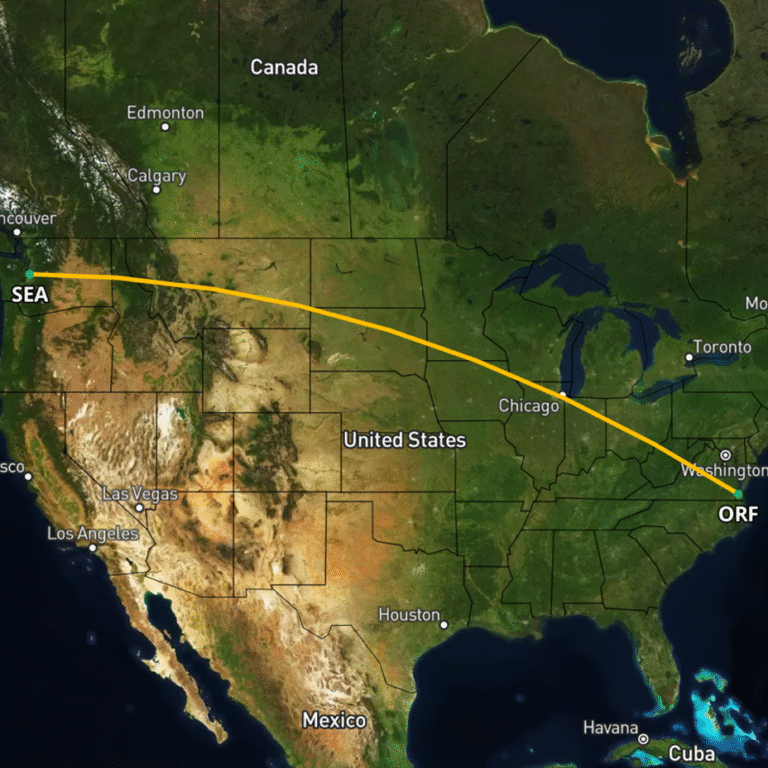

The Port Gamble S’Klallam Tribe is located on Puget Sound on the north end of the Kitsap Peninsula. For the last twenty of so years, I’ve taken the Edmonds-Kingston Ferry to Little Boston from Seattle.

It’s hard for me to describe Little Boston, mostly because Little Boston isn’t a place to me. It’s a kind of spiritual realm. I don’t mean spiritual in the ghostly or other worldly sense. More like a feeling. Like being home at Christmas. And it’s hard to give a detached description of a place like that, but I’ll do my objective best.

If you want a definitive history, go over to Tribal website. Or read The Strong People which provides an in-depth historical/cultural account of the S’Klallam people. Here’s my truncated version, with a ton of stuff left out and probably some inaccuracies.

Like all Puget Sound Tribes, prior to the arrival of white people, the Port Gamble S’Klallam people moved with the seasons to where they knew the fishing would good, the hunting, the berry picking, and the like. One of their more important seasonal village sites was “Teekalet” which was located right across the bay from their current tribal headquarters.

Trouble was that the newly landed white men wanted to build a sawmill on the village site. The year was about 1850 or so, and the S’Klallam people were forced to move. And they moved right across the bay onto a spit of land named Point Julia. As part of a war treaty, in 1855, the S’Klallam people, along with all other Tribes in the area, ceded their remaining land to the government (but wouldn’t give up their right to hunt, fish and gather in the region). As part of the treaty, the S’Klallam were supposed to relocate to the Skokomish Reservation but refused, ostensibly deciding to stay on Point Julia, work at the mill, hunt and fish the surrounding land and waters. At some point, the government gave up on trying to get the Port Gamble S’Klallams to relocate and established 1000 acres of land as the Port Gamble S’Klallam Reservation, to include Point Julia.

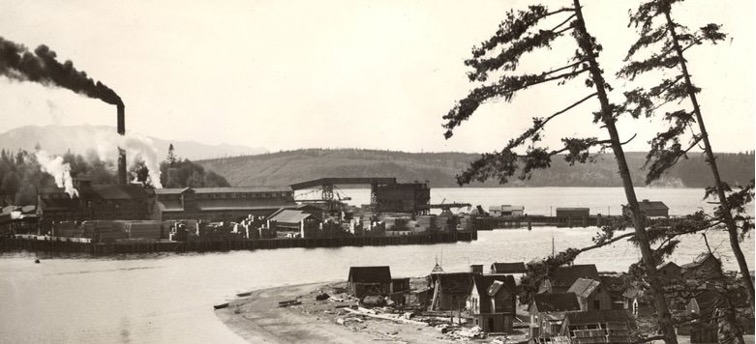

Below is old photo showing the mill and the Point Julia homes in 1937.

The Point Julia homes were built with lumber from the mill. For the mill owners, the Point Julia homes represented an extension of their company town at Port Gamble. Generations of S’Klallam would live on Point Julia as well as in company housing at the mill proper. Several S’Klallam workers would rise to be managerial level at the mill.

In the 1937 photo, the Point Julia homes had been standing for decades and pretty beat up by the weather and salty air. The homes were torn down soon after this picture was taken and Tribal Members moved upland to the bluff which is where this picture was taken.

A monumental court decision in the 1970s solidified the Tribe’s fishing rights, ruling that fifty percent of the annual fish harvest in Puget Sound would go to Puget Sound Tribes. This decision led to even grander fishing rights victories and ensured the financial future for Port Gamble S’Klallam and all other regional tribes. I’ve done a blog post on fishing because it deserves its own space. Better yet, get a copy of Ron Charles’s My Heart Is Good which is a definitive history of treaty rights, told through the life story of Port Gamble S’Klallam elder and former tribal chair Ron Charles.

In 2002, the Tribe opened its current casino. It’s a modest casino compared to many throughout Puget Sound, but it would allow the Tribe to start construction of its first traditional longhouse along with a library, senior center, and adult education center.

And it also allowed the Tribe to buy back over a thousand acres of their land lost in the Treaty, too.

And the future, as they say, looks bright.