A significant part of Blackbeard’s Lost Head is set in Hampton, Virginia, a place I grew up in.

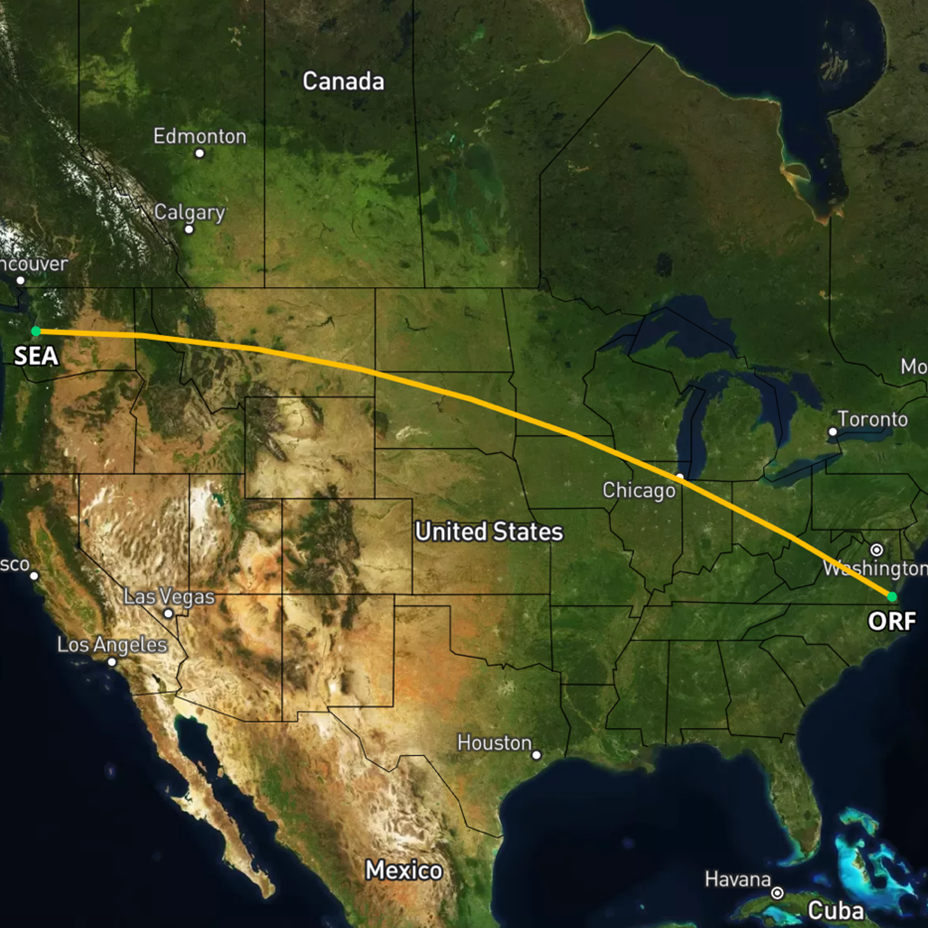

I left Hampton, Virginia for Seattle in 1987. I moved there to be with a girlfriend, and that didn’t work out, and then I was a stranger in a strange land. But the loneliness was washed away by Seattle. If Hampton was the oldest place in the country, Seattle had to be the coolest place in the country. Hordes of young people flocked to Seattle to hike and ski the mountains, kayak or sail Puget Sound, drink coffee, and now famously, check out the music club scene. In 1987, nobody had any idea that Seattle would end up hosting the mega corporations that make up the city today. Back then, you could still see and feel Seattle’s timber and fishing roots.

I had a boring job as an Urban Planner in Snohomish County just north of Seattle. I couldn’t see myself in a cubicle for the rest of my work life and decided I’d try another job on the Tulalip Reservation. I knew nothing of tribal communities. But the job description looked like something I could do and maybe I would have something more interesting to tell my grandkids besides laboring over memos and paperwork and meetings.

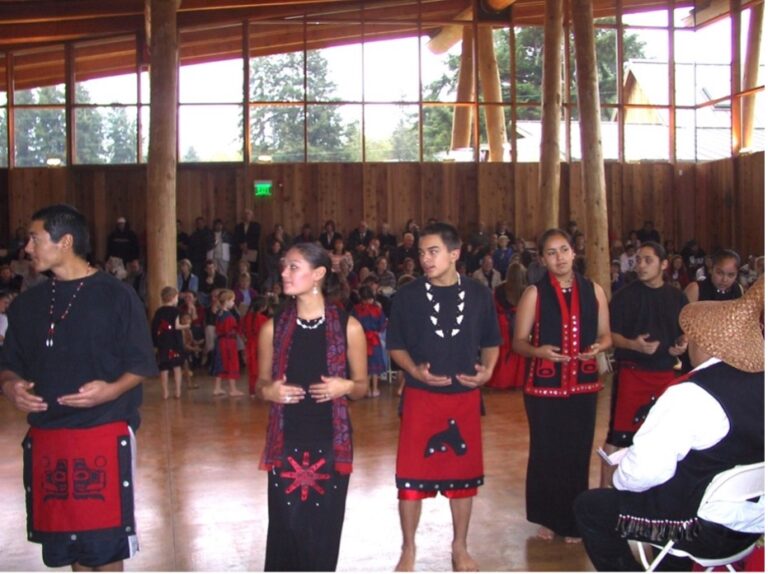

I was right. Sure, there were memos, paperwork and meetings, but there was a sense of purpose and community at Tulalip that was absent in my government job.

Looking back, I can honestly say that my time at Tulalip and Port Gamble S’Klallam Tribe (where I am today) has been a blessing. The people, places and events have shaped my life for the better and I am thankful for the experience. I’ve met some wonderful people and have made lasting friendships. Who could ask for anything more?

There is something that I need to say about my experience in the Pacific Northwest and Alaska working for Native people. The conventional academic, popular press, morbid view of Native Americans as people laboring futilely under historical trauma, unable to recover from the genocidal policies of colonizers is not what I witnessed in my thirty years working with tribes. I’m convinced it’s a view that benefits white people, but I haven’t given it much thought as to how. Maybe someone out there smarter than me can untangle that one.

The Tribal people I’ve known don’t dwell on the past, but they also don’t deny it either. My guess is that there’s a time and place for reflecting on the past, and there’s a time and place for reflecting on the future. My experience with Native people tells me that for them, the future gets the focus.

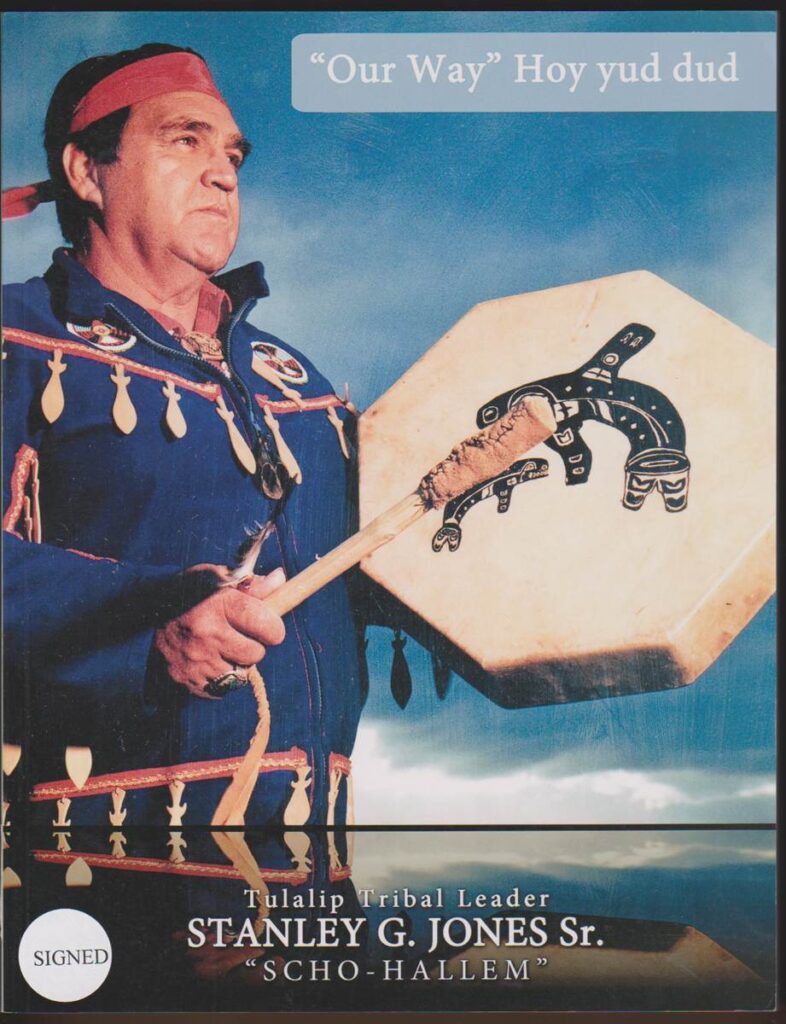

One of those leaders who refused to be told how he should feel about his history is Stan Jones. Or Chief “SCHO-HALLEM.” He’s a big part of my book, but not in any discernable way to readers.

When I met Stan Jones 1993, he was a towering figure at Tulalip and in all Indian Country. He was a Marine; battle tested in the Pacific Theatre of World War 2. He was a wise man. And a big man. He was a Snohomish Indian. Stan was one of those rare individuals who everyone knew by one name: Stan.

Like Eminem, Drake, Prince, or Adele.

Stan never talked to me. Even when in front of the Council, Stan never seemed interested in what I had to say or what I was doing. Not that I was upset about this. He was intimidating to me, and I didn’t want to get on his bad side by saying something I shouldn’t.

Then one day I went with several Tribal leaders to a meeting. I forget what the meeting was about, but I remember Stan getting tired of the bloviating, closed the meeting, then stood up and said, “it’s time for lunch.”

And as luck would have it, Stan slid into the chair directly across from me at the restaurant.

Stan looked at me and calmly asked, “Where you from Barrett?”

I’d learned to simply say Virginia. Because nobody’s ever heard of Hampton.

“I’m a transplant from Virginia,” I said.

“Hampton?”

I almost fell out of my chair. How the hell did he know about Hampton? Was he pulling my leg? Was he doing some Indian mind reading thing on me?

I was so stunned that I didn’t answer him at first but recovered and acknowledged that his instincts were indeed right on the money. I grew up in Hampton and even went to Phoebus High School.

“My father went to Hampton Institute for college,” Stan tells me. “I never went to college. I’m assuming you go back to visit your family. When you go back, can you stop by the university and get me a letterman’s jacket? I’ve always wanted a letterman’s jacket.”

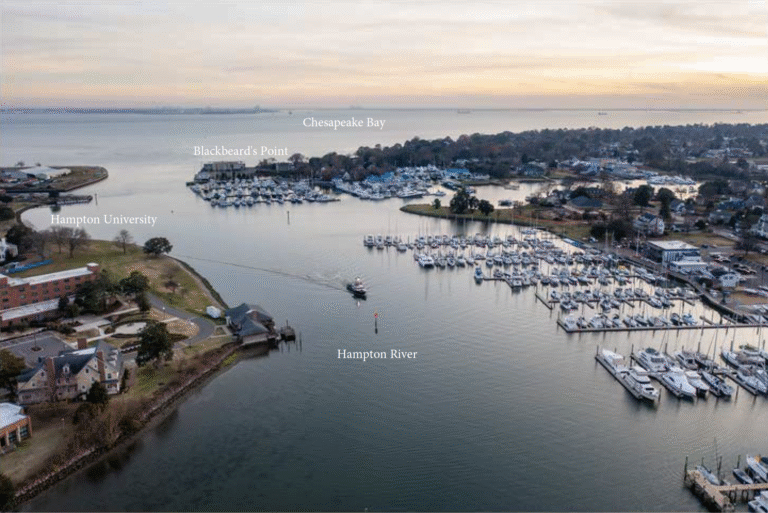

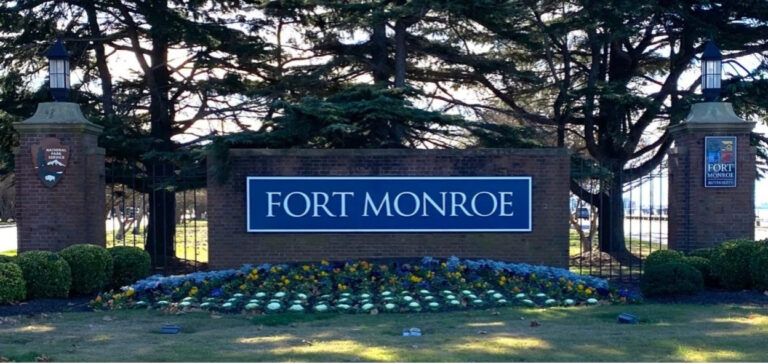

Now, if you are standing on Blackbeard’s Point, just across the river is Hampton University, its bucolic waterfront campus within swimming distance on a calm day. The school was built in 1868 (150 years after the Blackbeard incident) to further the education of formerly enslaved people just after America’s bloody Civil War. Students applied for admission and were selected based on academic achievement. Over the years, the school went from Hampton Agricultural and Industrial Instituteto Hampton Institute, and today Hampton University. The university is one of several Historically Black Colleges and Universities or HBCUs) located primarily in the southern part of the United States. The founding of Hampton University is a fascinating story and for the times, a remarkably story of resilience and courage.

I knew the university well. My high school was attended by several of my classmates that were the sons and daughters of Hampton’s professors, administrators and coaches. But I never stepped foot on the university as a kid. It was a scary place with adults and austere institutional buildings that represented anything but a good time.

But of course, now at age 30 and a veteran of college campuses, I had nothing to fear and agreed to do as Stan Jones asked without hesitation.

That Thanksgiving, I went home to be with my family and drove over the Hampton University Student Bookstore.

I struck up a conversation with the bookstore clerk, explained that I worked for an Indian Tribe and I needed an XL letterman’s jacket for the Tribal Chair whose father went to HU back in the early twentieth century. Maybe XXL.

We bonded over a few families and acquaintances we both knew. As I was leaving, he encouraged me to visit the university museum where, as luck would have it, there was an exhibit of art made by the Native Americans who attended the school over a hundred years ago.

I made my way to the museum (it was free then and still is) and immediately stood flabbergasted by the beauty and spirit of the Indian art displayed on the main floor. I drifted about, taking in the beautifully crafted masks, hats, clothing, dolls and such. I then struck up a conversation with one of the museum guides, explained why I was holding a letterman’s jacket, and out of the blue, was invited into the basement of the museum.

It was in the basement of the Hampton University Museum that gave me the idea to write Blackbeard’s Lost Head.